Indoor Testing

In Iceland, it is pretty hard to fly drones outside for about 6 months of the year, when you are trying to do experiments in autonomous flight. The sea winds, freezing temperatures, and unpredictable rain and snow always get in the way. This is all not to mention that Reykjavik University is right next to Reykjavik Airport, so it is illegal according to Icelandic law to fly any drone with a mass of 2kg or more, and illegal to fly above the height of the tallest surrounding buildings. In any case, even though it may be technically legal to fly something like a DJI Mavic near the no-fly zone (especially indoors), the drones will not arm if they learn their positions (even approximately) via either GPS or location services provided by WiFi to the phone or tablet that you use to view the drone’s video. Moreover, GPS accuracy tends to be low here (i.e. GDOP is high) because of Iceland’s distance to the equator, so it is hard to control a drone with purely GPS-based navigation as in the case of many custom-made ArduPilot or PX4 drones. So, we have been testing autonomous flight algorithms on a small DJI Spark (shown above, banana for scale). It has very stable flight performance for the most part, and is too small to hurt anyone or damage anything if it crashes.

The goal of this part of the PhD is to create a fiducial landing algorithm that uses a gimbal to aim the camera at the marker for tracking, and can run on embedded hardware onboard the drone. Unfortunately, the DJI Spark does not have onboard processing hardware that we can access, so we have to jump through a lot of hoops to get it to work. DJI does provide a Mobile SDK that allows you to programmatically do a lot of things – essentially everything you can do with the controller itself. The things that we are interested in are offloading video frames for external analysis and providing programmatic control based on that analysis. Unfortunately, DJI forces you to use its normal paradigm of app-based interaction with the drone. I suppose this can be useful because it provides a touchscreen and such, but ultimately it tends to get in the way for a number of reasons which I will explain below. We have made an app that is based on some of the video decoding sample and the virtual sticks sample that DJI provides. The video decoding sample provides the means for sending individual frames to an external board (Raspberry Pi 4) for processing, and the virtual sticks example gives a way of programmatically controlling the drone.

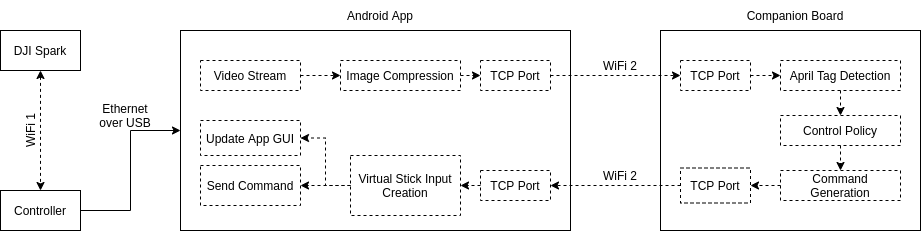

The (necessarily horrible) architecture of the system is shown below.

The DJI Spark and its controller talk to each other with no outside intervention from us. Using an Ethernet over USB connection, our Android app decodes frames from the video stream, compresses them, and sends them the companion board (Raspberry Pi 4) over a Wifi connection from the Raspberry Pi 4. (The Raspberry Pi is set up as a WiFi access point.) The Raspberry Pi then analyzes the video frames using fiducial marker software (in this case, April Tag 24h10), generates a control command based on a policy that we have created, and then sends that command back to the tablet. The tablet creates a VirtualStick command from the control output it receives, then sends it to the drone (via the controller) and updates the GUI so we can see what the control system is trying to do in real time. The sliders around the video show what each of the VirtualStick inputs are doing:

- Left: throttle

- Top: yaw

- Bottom: roll

- Right: pitch

- Far right: gimbal tilt

In our system, the VirtualStick inputs are mapped to velocity targets in the drone’s local coordinate system, so that a positive value on the pitch stick translates to a forward target velocity. Similarly, a positive value on the roll stick translates to a target velocity to the right, etc. with the rest of the sticks.

We set up the system to do the following steps in flight:

- takeoff

- find takeoff landing pad and precision hover over it

- search for the other landing pad

- approach the landing pad and precision hover over it, while tracking it with the gimbal-mounted camera the entire time

- descend over the landing pad, keeping it in view the entire time

- once reaching the DJI-enforced minimum altitude, commit to the landing

- repeat, alternating the landing pads used as takeoff and landing locations

A demo is available below, using our custom April Tag 24h10 system. The system achieved a video processing rate of only about 6-7 Hz, bottlenecked by the image compression on the tablet, and its transmission over WiFi to the Raspberry Pi. It is subject to orientation ambiguity, though less than expected. This can be seen in the “flickering” of the control inputs on the app, and sometimes in corresponding, quick, erratic behavior of the drone.